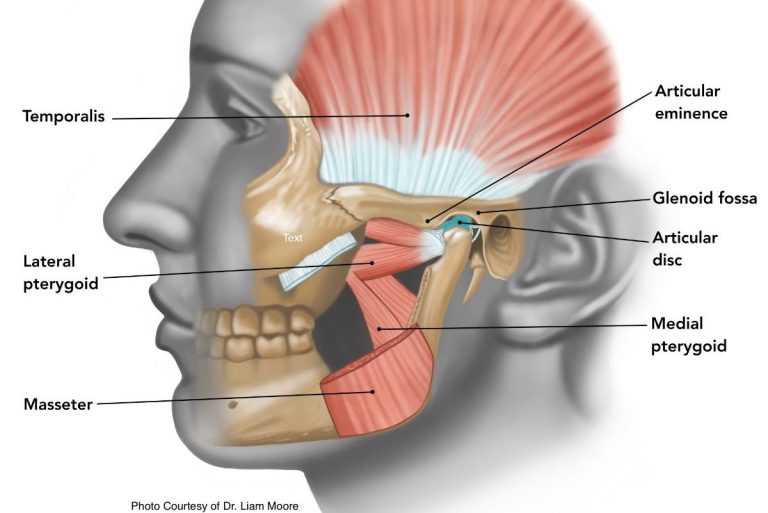

The temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) refers to the two joints located on either side of your face that connect your jaw to your skull. Pain in this area can stem from muscle tension, joint inflammation, or structural damage to the cartilage and bones of the joint.

Treatment options may include soft tissue release, gentle joint manipulation, or strengthening exercises for the muscles surrounding your neck and face. Occasionally TMJ pain will require imaging and specialist referral for surgery or orthodontic braces to help support the joint.

Symptoms of TMJ pain and dysfunction

TMJ pain can manifest as an ache in the jaw or face and may also lead to headaches. Dysfunction of the TMJ can result in clicking or locking of the jaw, often occurring while eating or chewing, but it can also happen upon waking or at rest.

Stiffness or dysfunction in this joint may limit jaw movement, making it feel as though you can’t fully open your mouth. Additionally, you might experience the sensation that your teeth are misaligned or don’t come together properly when chewing.

Causes of pain

TMJ dysfunction can result from tension in the muscles surrounding the jaw, including those involved in chewing and moving the mouth, as well as neck and shoulder muscles that connect to the base of the skull. The alignment of your head and neck can influence the position of the jaw and the effectiveness of these muscles. Consequently, posture can play a significant role in TMJ-related issues.

Stress

Stress can lead to tension in the muscles around the neck and shoulders, negatively impacting posture and jaw function. Grinding your teeth or clenching your jaw is often a sign of stress, leading to overuse of the jaw muscles and resulting in pain.

Posture

i. Sleeping

Sleeping posture can contribute to jaw dysfunction. For instance, sleeping on your stomach can place your neck and jaw in an unfavorable position, causing stiffness and pain over time.

ii. Sitting

Sitting posture also plays a role; when your head is positioned forward on your neck—common in slumped postures—it can create tension in the muscles under the jaw, leading to discomfort.

ii. Exercising

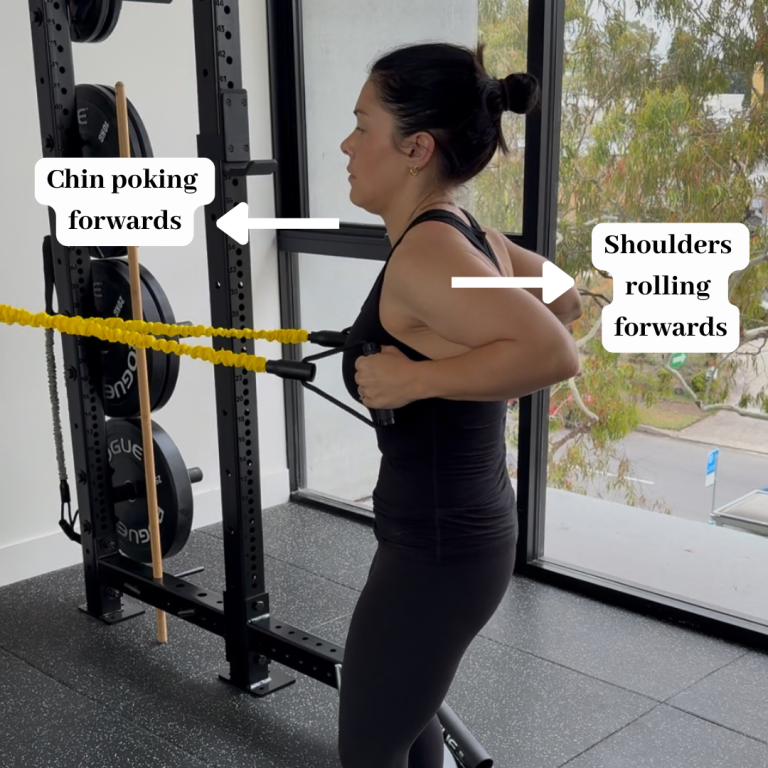

Additionally, exercise posture can affect jaw health in several ways. Maintaining tension in your jaw or clenching your teeth during workouts can lead to muscle overuse and fatigue, resulting in jaw pain. Poor movement patterns can also increase strain on your shoulders and neck, which can further contribute to tension and discomfort in the jaw.

Structural causes

Damage to the cartilage ring within the joint can lead to clicking and locking. This damage may be degenerative, resulting from years of teeth grinding, poor posture, or genetic factors, or it could stem from an acute injury, such as a blow to the jaw or biting down on something hard.

Arthritis in the TMJ can also result in stiffness, pain, or clicking. While the incidence of arthritis is largely influenced by genetics, poor joint function over time can accelerate the degeneration process.

Physio treatment

Physiotherapists employ various techniques to alleviate TMJ pain. These may include soft tissue massage for the muscles around the neck and jaw, and occasionally the shoulders, if they contribute to jaw tension. Specific jaw releases can be applied if one side is tighter than the other. If motor control issues are contributing to jaw pain, physiotherapists will provide targeted exercises to improve strength and movement in the jaw.

Posture in the head, neck, and shoulders plays a significant role in jaw pain. For instance, rounded shoulders or a slumped posture can increase tension in the muscles that connect to the base of the skull and jaw. Physiotherapists can identify poor postures and prescribe exercises to strengthen the relevant muscles and correct these patterns. They are also skilled in assessing your workspace and recommending modifications to improve your posture. For desk-related jobs, reviewing your desk setup, chair, monitor, and devices can help alleviate posture-related tension. For physically demanding jobs, evaluating your working postures, tools, and movement patterns can ensure your body is positioned favorably to prevent muscle fatigue, tension, and jaw pain.

If sleep posture is identified as a contributing factor to TMJ pain, adjustments to your sleep position, along with the use of specialized pillows or mattresses, may help manage discomfort.

TMJ specialists, dentists, or orthodontists may recommend braces to improve jaw alignment, reducing undue stress on the jaw and alleviating the effects of teeth grinding. In some cases, Botox injections may be suggested to decrease muscle activity around the jaw that contributes to pain, while surgery might be necessary if the cartilage needs to be repaired, removed, or replaced.

Psychologists can assist with stress management, which may help reduce instances of teeth grinding and jaw clenching.

TMJ pain can arise from a variety of causes and therefore require specific assessment and a targeted treatment approach. If you feel you are experiencing TMJ pain, make an appointment with us today.